Featured Range

Schmincke’s HORADAM® Naturals is a 100% vegan, eco-friendly watercolour line featuring 16 matte, semi-transparent colours made from natural earth and plant pigments. These paints blend the fluidity of watercolour with the control of gouache, offering subtle granulation and a gentle aroma. Rewettable after drying, they’re ideal for expressive, earth-toned work and compatible with all watercolour and gouache techniques. Available in 15 ml tubes and themed trios.

Discover Now

FIND YOUR PERFECT COLOUR

Welcome to colour exploration, Parkers style. Below you’ll find our range organised into easy, clickable accordion menus, grouped by popular categories and brands, each with product and range images to guide the eye. Think of it as opening drawers in your own, very well stocked studio. Click to expand, browse, compare, then click again to close and move on. Click a product range icon to explore the full range. Return to this page at any time as the homebase of our complete colour range.

Featured Range

Schmincke’s HORADAM® Naturals is a 100% vegan, eco-friendly watercolour line featuring 16 matte, semi-transparent colours made from natural earth and plant pigments. These paints blend the fluidity of watercolour with the control of gouache, offering subtle granulation and a gentle aroma. Rewettable after drying, they’re ideal for expressive, earth-toned work and compatible with all watercolour and gouache techniques. Available in 15 ml tubes and themed trios.

Discover NowWHY THIS MATTERS

Understanding how pigments are bound helps explain why each medium feels the way it does, and why we respond to them differently as artists. Some invite revision, others demand commitment. Some reward speed, others patience. At the end of the day, every colour we use is pigment plus binder, but the magic lies in how those two elements are brought together. Exploring that relationship is part of the joy of making art, and part of discovering which materials truly speak your language.

READ MORE

Core Artist Brush Shapes

At the foundation of all brushwork are the universal shapes every artist encounters. Rounds offer unmatched versatility, shifting from hairline detail to broad strokes through pressure alone. Flats provide structure, strong edges and confident planes of colour. Filberts soften those edges, making them ideal for modelling form, flesh and atmospheric passages. Brights, with their shorter hair, deliver control and strength for thick paint and precise placement. These shapes form the backbone of brush literacy. Once understood, they allow artists to translate intention into mark with confidence, regardless of medium.

Fibre Choice & Shape: The Artist’s Decision

Ultimately, shape and fibre work together. A Rigger in soft squirrel behaves very differently from one in springy synthetic. A Filbert in hog bristle pushes paint aggressively; in soft synthetic, it blends gently. Modern brushmaking gives artists more choice than ever—natural hairs for tradition and sensitivity, synthetics for durability, ethics and consistency, and blended fibres for a balance and optimisation of both. Understanding specialised shapes and fibre, empowers artists to choose tools intentionally, reducing frustration and unlocking techniques that feel effortless rather than forced.

Watercolour & Fluid Media Specialists

Watercolour rewards brushes that manage flow, timing and edge quality. Pointed rounds dominate because they combine a fine tip with a generous belly. Mops and wash brushes excel at large, even passages and pre-wetting paper. Hake brushes, often goat hair or soft synthetics, are perfect for skies, lifting and controlled flooding. Daggers and sword liners introduce calligraphic variation, while flat wash brushes define architecture and horizon lines. In fluid media, brush shape directly influences rhythm and restraint—choosing the right specialist tool can dramatically improve clarity and confidence.

Stiff Brushes for Texture & Preparation

Certain brushes exist to withstand physical work. Hog bristle brushes dominate oil painting for their strength, resilience and ability to move thick paint. Stencil brushes, with short, firm hair and flat tops, are ideal for stippling, dry-brush effects and controlled texture. Gesso and ground brushes are built wider and tougher, designed to scrub primer into canvas or panel. Modern stiff synthetics now rival bristle for durability while offering easier cleaning and consistency. These brushes aren’t about subtlety—they’re about building structure, energy and surface integrity.

Riggers, Liners & Script Brushes

Riggers (also called liners or script brushes) are defined by their long, narrow hair and fine point. Originally developed for painting ship rigging, they excel at continuous lines—branches, grasses, wires, calligraphy and signature marks. Their length allows paint to flow smoothly without frequent reloading, encouraging expressive, uninterrupted strokes. In oil and acrylic, riggers are invaluable for linear accents and final detailing. In watercolour, they demand confident timing and pressure control. These brushes reward decisiveness and are best used sparingly—but when mastered, they add elegance and energy to a painting.

Mottlers, Wash Flats & Large Surface Brushes

Mottlers are wide, flat brushes with long, soft hair, traditionally squirrel or modern soft synthetics. They are designed for large, even applications—backgrounds, skies, glazing and varnishing. Unlike expressive brushes, mottlers aim to leave no visible stroke. Large wash flats and decorator-style brushes serve similar roles across acrylic and oil, especially when toning grounds or laying broad colour masses. Artists working large-scale or atmospheric compositions rely on these tools to establish unity early in a painting. Their success lies in capacity, softness and even release—not finesse.

Overgrainers, Fitches & Decorative Specialists

Some brushes originate in decorative and faux-finishing traditions but remain powerful fine art tools. Overgrainers are long, soft flats designed to drag, blend or texture paint subtly—excellent for wood grain effects, soft transitions and layered atmospheres. Fitches are short, flat brushes used for precision edging, glazing and controlled blending. Fan brushes, often misunderstood, are specialised tools for feathering edges, breaking up marks and creating organic textures like foliage or hair. These brushes encourage experimentation and restraint; used thoughtfully, they add nuance without overpowering a composition.

As a practising artist, I’ve learned—sometimes the hard way—that how you care for your brushes has as much impact on your work as the brushes themselves. A beautifully made brush is a precision tool, and whether it’s a prized Kolinsky round, a favourite filbert, or a tough synthetic workhorse, good cleaning habits can mean the difference between a brush that lasts years and one that’s ruined in weeks. Across all mediums, brush care isn’t complicated—but it does demand consistency and respect.

The golden rule: never let paint dry in the brush

This is the most important principle, regardless of medium. Dried paint creeps into the ferrule, forcing hairs apart and destroying the brush’s shape from the inside. Once paint dries there, no amount of cleaning will truly restore the brush. Even during long painting sessions, get into the habit of rinsing brushes regularly and reshaping them between passages.

Watercolour brushes - especially those made from natural hair or high-end synthetics—are delicate instruments. After each session, rinse thoroughly in clean, lukewarm water until it runs clear. Avoid hot water, which can soften glue inside the ferrule and damage fibres. For natural hair brushes, a mild brush soap used occasionally will remove residue and help maintain spring and point.Gently reshape the tip with your fingers and allow the brush to dry horizontally or with the head pointing downward. Never stand a wet brush upright—water can seep into the ferrule and weaken the binding. With good care, a quality watercolour brush can remain razor-sharp for years.

Oil painting - demands more robust cleaning, but also more care than many artists realise. The common mistake is relying too heavily on harsh solvents. While mineral spirits or turpentine will remove oil paint, overuse strips natural oils from the hair and shortens the life of the brush.My approach is to wipe excess paint thoroughly on a rag first—this step alone removes most of the paint. I then use a small amount of solvent only if needed, followed immediately by proper soap and water. Brush soaps designed for artists are ideal, but a gentle, natural soap can also work. Work the soap gently into the hairs, rinse thoroughly, and repeat until the water runs clear.Always reshape the brush before drying. Hog bristle brushes in particular benefit from careful reshaping, as splayed bristles affect paint handling. Store clean, dry brushes flat or upright only once fully dry.

Acrylic paint - is the most unforgiving medium when it comes to brush care. Once it dries, it’s permanent. That means vigilance is essential. Keep brushes wet while working and never leave them standing in water—this bends fibres and encourages paint to creep into the ferrule.Clean acrylic brushes immediately after use with water and mild soap. For stubborn residue, specialised acrylic brush cleaners can help, but prevention is far better than cure. Many artists choose durable synthetic brushes for acrylic work precisely because they tolerate frequent washing and tougher handling.

Gouache - behaves much like watercolour but can dry more stubbornly due to its opacity. Clean brushes promptly and thoroughly, using gentle soap when needed. Mixed media artists should be especially attentive—switching between inks, acrylics, mediums and collage adhesives can leave unexpected residues. When in doubt, wash the brush sooner rather than later.

Special brushes for Varnish and Grounds - Some brushes deserve single-purpose dedication. Varnish brushes should never be used for paint, as even small residues can ruin a smooth finish. Clean varnish brushes immediately with the appropriate solvent, followed by soap and water, then store them carefully to protect their soft edges.Gesso and ground brushes are workhorses, but they still need proper cleaning. Scrub out primer thoroughly before it dries, reshape, and allow to dry fully. Even tough brushes last longer with basic care.

Storage and long-term care

Once clean and dry, store brushes with care. Avoid crushing heads in jars or drawers. Brush rolls or cases protect shapes, especially for travel. For natural hair brushes, occasional conditioning with a dedicated brush soap helps maintain suppleness.

Caring for brushes isn’t just maintenance—it’s respect for your tools and your practice. A well-cared-for brush responds better, feels more predictable, and ultimately helps you paint with greater confidence. Expensive brushes earn their value over time, and good care ensures they continue to reward you every time they touch the surface.

Hopefully this information has helped to inform you of your options and best fit for finding the brushes you need.

SHOP NOW BY TYPEAs artists, we spend a lifetime learning colour, how it behaves, how it feels, and how it comes into being. Beneath every tube, pan or stick lies the same fundamental ingredient: pigment. What transforms that pigment into oil paint, watercolour, acrylic or pastel is the binder that holds it together. Understanding these differences doesn’t just satisfy curiosity, it deepens the way we paint, choose materials and connect with the medium itself.

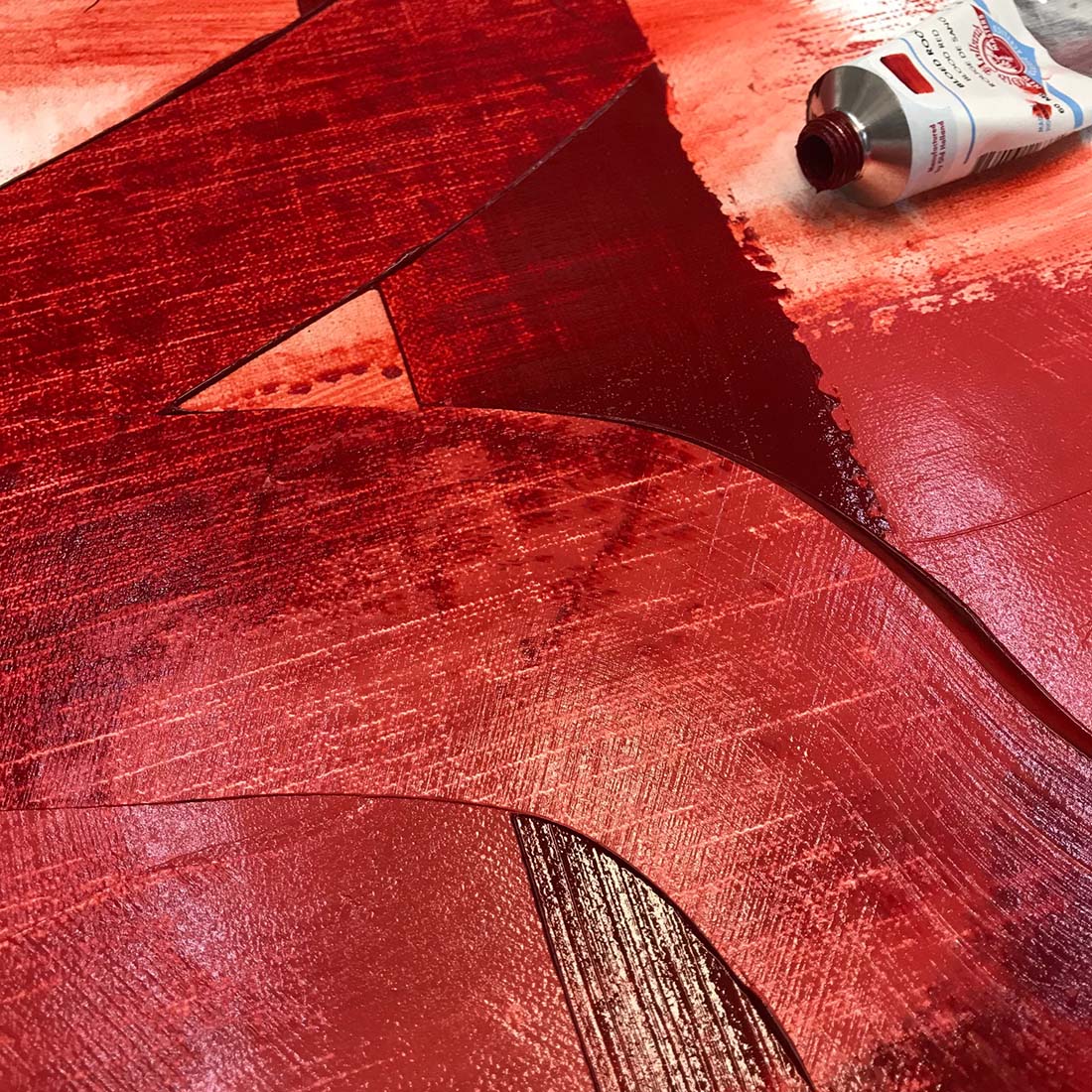

Oil Colour: Pigment and Oil, a Slow Conversation

Oil paint is perhaps the most historically resonant medium, and its simplicity is deceptive. Finely ground pigment is bound with a drying oil, traditionally linseed, but also walnut, poppy or safflower depending on colour and desired properties. This oil doesn’t evaporate; it oxidises and polymerises, forming a flexible paint film over time. That slow drying process is what allows oils their unmatched blending, depth and subtlety. Different oils influence colour clarity, drying speed and texture, which is why oil paint can feel buttery, ropey, glossy or velvety depending on formulation. For the artist, oil colour is about patience and physicality, pushing, pulling and revisiting paint as it gradually settles into permanence.

Watercolour: Pigment Suspended in Light

Watercolour is built on restraint. Pigment is finely dispersed in a water, soluble binder, traditionally gum arabic, sometimes modified with honey, glycerin or sugar derivatives to influence flow and rewetting. Unlike oil, the binder here dries by evaporation, leaving pigment delicately adhered to the paper’s surface. There is no thick film, just colour and light interacting through paper fibres. This is why watercolour feels so immediate and unforgiving: once the water is gone, the decision is made. Understanding the binder helps explain why some watercolours granulate, others stain, and why rewetting behaves differently across brands. For artists, watercolour is about timing, gravity and trust.

Acrylic Colour: Pigment Locked in Polymer

Acrylic paint is the most modern of the major paint families, yet it’s built on an elegant idea. Pigment is suspended in an acrylic polymer emulsion, tiny plastic particles dispersed in water. As the water evaporates, these particles fuse into a tough, flexible film that permanently locks the pigment in place. This explains acrylic’s speed, durability and versatility. It can behave like watercolour when diluted, oil when used thickly, and something entirely its own when layered or textured. The binder is inherently stable, non, yellowing and water, resistant once dry, making acrylic a favourite for contemporary practice. For artists, acrylic is about adaptability and immediacy, fast decisions, fast surfaces, endless possibilities.

Pastels: Pigment at Its Most Direct

Pastels are often described as “pure pigment,” and while that’s a romantic simplification, it’s close to the truth. In soft pastels, pigment is held together with a very minimal amount of binder, often gum tragacanth or methyl cellulose, just enough to form a stick. There’s no liquid vehicle, no film, no drying time. What you apply is almost entirely pigment resting on the surface of the paper. Oil pastels, by contrast, use a non, drying oil or wax binder, creating a creamy, blendable mark that never fully hardens. Pastels reveal pigment in its rawest, most tactile form, reminding artists that colour doesn’t always need a vehicle to be powerful.

Gouache: The Opaque Cousin

Gouache sits between watercolour and bodied paint, as, object. Pigment is bound with gum arabic like watercolour, but with added chalk or inert fillers to create opacity. This changes everything. Light no longer passes freely through the paint; it reflects back, giving gouache its velvety, matte finish. Colours dry lighter, edges can be reworked, and shapes can be corrected, making gouache a favourite for illustration and design. For artists, gouache is about control and clarity, offering the immediacy of watercolour with a painterly authority of its own.

Graphite: Carbon, Refined

Graphite is pigment without binder in the traditional sense. It’s a crystalline form of carbon mixed with clay to control hardness. More clay means harder, lighter marks; less clay means softer, darker ones. There’s no drying, no adhesion beyond physical contact with the paper’s tooth. Graphite reminds us that not all mark, making is about paint films, sometimes it’s about friction, pressure and subtlety.

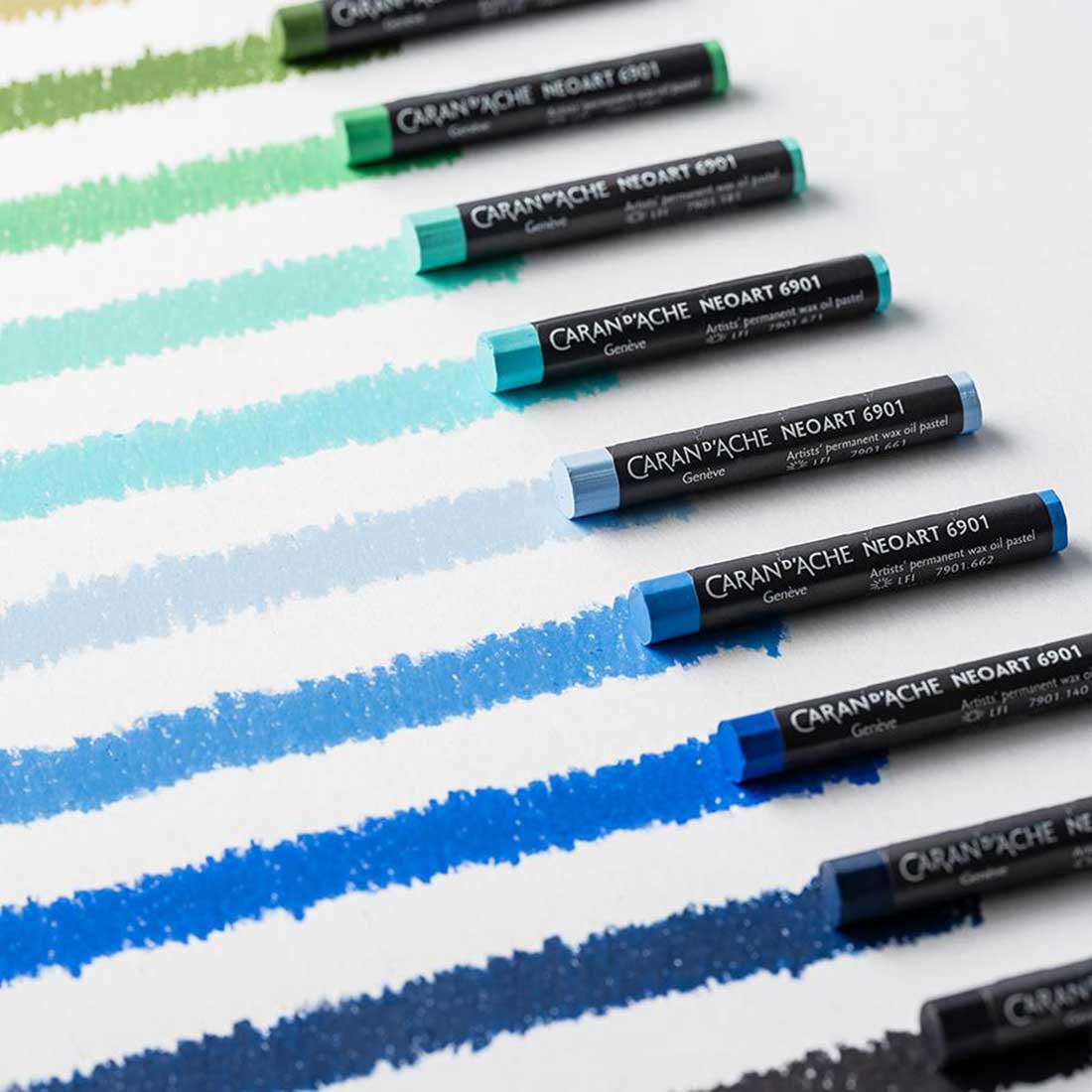

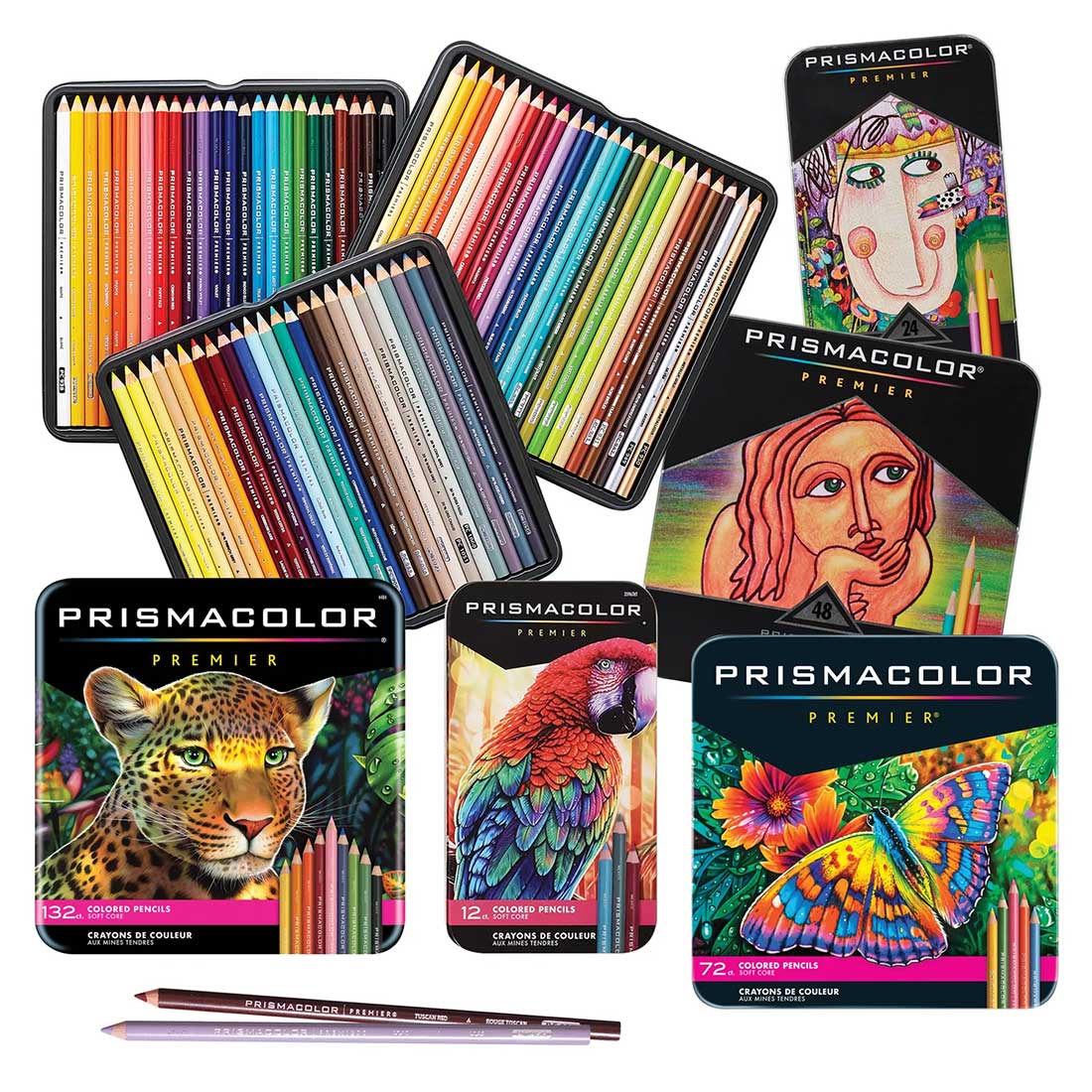

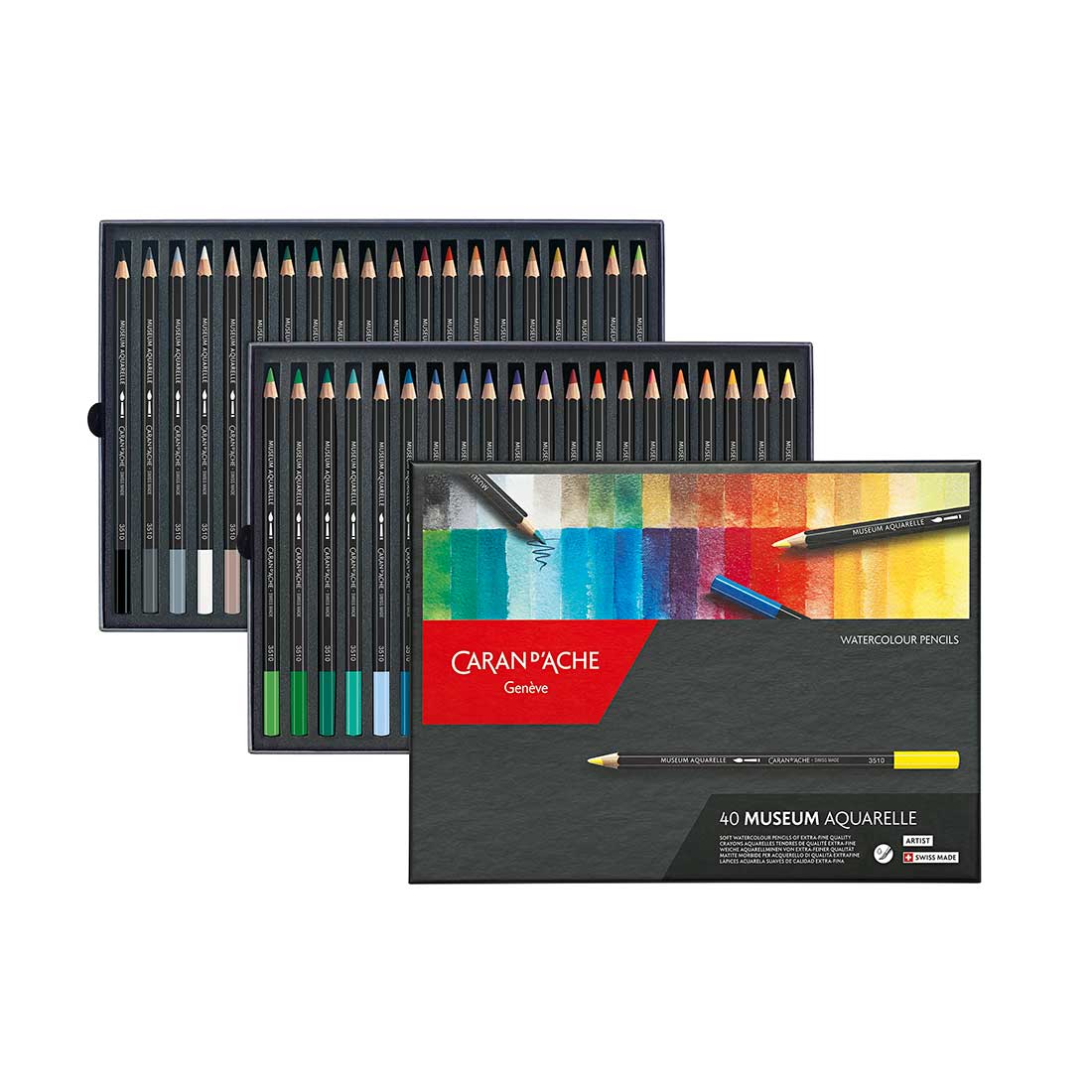

Coloured Pencil: Wax, Oil and Precision

Coloured pencils use finely ground pigment bound with either wax, oil, or a hybrid binder. Wax, based pencils tend to be softer and more opaque but can develop “wax bloom” over time. Oil, based pencils are generally firmer, allowing for sharp detail and layered transparency. In both cases, the binder allows pigment to be deposited gradually and precisely, building colour through repetition rather than gesture. For artists, coloured pencil is about patience, layering and intimate control.

Charcoal: The Elemental Mark

Charcoal is one of the oldest artist materials, made by burning organic material, often willow or vine, in a low, oxygen environment. Like graphite, it has no true binder. Its particles cling loosely to the surface, creating marks that are rich, expressive and easily altered. Fixatives can be applied later to lock the pigment down, but charcoal’s beauty lies in its fragility. It’s a medium that celebrates impermanence and process.

RETURN TO TOP NAVIGATIONSUBCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Be first to discover all our New Products, Promotions and great product information.

Sorry, there are no products in this collection.